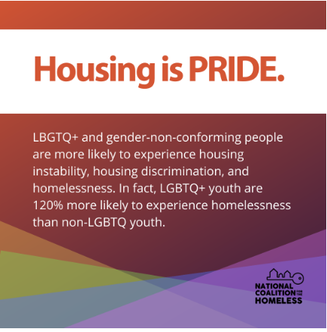

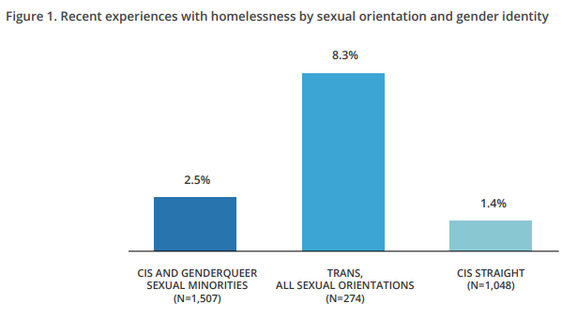

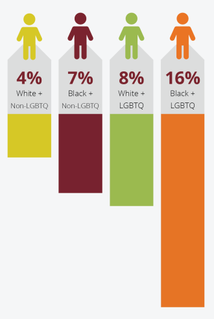

Image from NCH.org Image from NCH.org by Nathaniel Hagemaster While it’s common knowledge that black people are highly overrepresented in homeless populations, fewer people know that members of the LGBTQIA community face similar adversity. Research is now showing that the long-held prejudices that keep minorities vulnerable to poverty contribute to homelessness among black and LGBTQIA populations, with a particularly intense impact where those populations overlap.  Image from Chapin Hall Image from Chapin Hall According to recent studies (listed at the bottom of this post), people who are queer encounter more and sometimes unique obstacles to stable housing than others. For example, queer youths are more likely to have to flee abusive home situations or to be disowned by their families. Trans people are more likely to face transphobic discrimination, which creates obstacles to employment, safety, housing services, etc. Racial minorities in the queer community are bound to face racial discrimination in addition to homo- and transphobia, increasing the risk of poverty and housing insecurity. This blog summarizes research about the unique challenges that influence homelessness within the LGBTQIA community and predicts how 2023 anti-LGBTQ legislation might impact the future of queer homelessness, especially for youths. Homeless Queer Youth The National Coalition for the Homeless (NCH) finds that LGBTQ teenagers are highly overrepresented in the homeless populationa: 40% of homeless youth identify as LGBTQ, while the general youth population is only 10% LGBTQ (NCH). A common occurrence is that parents abandon their teenage sons/daughters when they discover their queerness. 68% of the youths that received homeless services have faced rejection by their families and 54% have reported physical, emotional, or sexual abuse within their families (NCH). Members of the LGBTQIA community who come out as youth risk being disowned by their families and likely won’t have anywhere else to go with no resources with which to be financially independent. We often assume that parents reject and displace their children as soon as they learn about their LGBTQIA identification; however, the path to youth homelessness is more complex. A teen’s sexual orientation and/or gender identity is often just one of many factors that lead to their homelessness. A study from Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago found that, even though coming out of the closet is a major factor to youths facing rejection, escalating conflicts with parents over time are what lead to queer youth homelessness (Chapin Hall). In most cases, some combination of familial poverty, abuse, addiction, mental health struggles, or housing issues lead to a queer youth’s eventual abandonment (Chapin Hall). To address the increased risk of homelessness for queer youth, NCH proposes that schools serve as "safe havens" for all students; therefore, bullying of queer youth should be aggressively addressed and the education of homeless students should be ensured (NCH). Unfortunately, Don’t Say Gay legislation would obligate school staff to report queer student behavior to parents or guardians and prohibit discussions of queerness. Many schools will not be able to serve as safe havens, as a result, since the proposed Don't Say Gay policies would eliminate any trust that schools could cultivate with students. Such legislation would limit schools' ability to prevent youth homelessness and ultimately make schools unsafe for LGBTQIA youth.  Image from Williams Institute Image from Williams Institute Homeless Trans People Like with any queer youth, trans youth can face parental abandonment; however, homeless trans people in general also face additional persecution that cisgender people don’t. Trans or gender-nonconforming people are more likely to experience homelessness than queer cisgender people (NCH); and nonbinary people are more likely to experience homelessness than gender-conforming men and women of any sexual orientation (Williams Institute). Trans youth tend to spend almost twice as much time (52 months) homeless and away from their families than their cisgender, heterosexual peers who spend about 26 months away from their families (NCH). Transgender people are also likely to get turned away from shelters, abused within shelters, and face danger when they are placed with members of the sex that they were assigned at birth (NCH). More than half of trans adults who access homelessness services face sexual or other kinds of harassment by staff or other residents (NCH). In 2016, HUD revised their policy to ensure equal access to shelter programs for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals, but shelters and service providers that aren’t federally funded don’t have to follow these policies (NCH). Considering the anti-trans slant in recent legislation, it seems as though many states won’t be hospitable to homeless trans people if they aren’t legally obligated to.  Image from Chapin Hall Image from Chapin Hall Homeless People of Color Just as youth and trans members of the LGBTQIA community experience greater levels of homelessness than older and non-trans members, black members of the LGBTQIA community are more likely to experience homelessness than their non-black peers. Research shows that almost a fourth of LGBTQIA black men between the ages of 18 and 25 have reported recent homelessness, which is almost double the rate for queer white men of the same age group (which is higher than the rate for black and white heterosexual men) (Chapin Hall). As people who belong to more than one “high-risk subgroup,” young, black, male members of the LGBTQ community had the highest rates of homelessness (Chapin Hall). The US Transgender Survey found that 30% of trans respondents reported experiencing homelessness and 42% of them were black (USTS). There’s a definite need to address housing instability among black queer people in ways that include, but aren’t limited to, LGBT advocacy frameworks (Williams Institute). Therefore, it’s suggested that homeless service programs become more accessible to LGBTQ youth of color in black neighborhoods (Chapin Hall). Considering how black queer people are the demographic that’s most at-risk of homelessness, measures must be taken to ensure the safety of this community and access to homeless services. Conclusion

In their executive summaries, NCH and Chapin Hall suggest solutions to the issues that they address. However, most laws under the Don’t Say Gay bill will likely work against several of these solutions to the issue of homelessness among queer people, especially youth. For example, it’s suggested that service providers find allies within queer homeless youths’ families, as well as helping these youth establish connections with peers and adults that are members of the LGBTQIA community to help them feel accepted and provide general guidance (Chapin Hall). However, under these new laws, parents who aid their trans or nonbinary child’s gender confirmation are liable to get charged with child abuse. The legislation also aims to prevent queer staff at schools from disclosing their queerness, which will likely prevent any chances of mentorship within the LGBTQIA community. Preventing opportunities for queer faculty or staff from coming out could cause queer youth to distrust adults, especially when they become responsible for outing youths to their parents. This increased distrust among youths would limit the reach that any adult could have with them, which would ultimately limit the resources for at-risk or homeless youths. For more information about recent anti-LGBTQIA legislation, please visit the Human Rights Campaign website. ________________ Works Cited James, S. E., Brown, C., & Wilson, I. "U.S. Transgender Survey: Report on the Experiences of Black Respondents." USTransSurvey.org, TransEquality.org, NBJC.org, BlackTrans.org. 2017, Washington, DC and Dallas, TX: National Center for Transgender Equality, Black Trans Advocacy, & National Black Justice Coalition. Accessed 15 June 2023. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Black-Respondents-Report.pdf Morton, M. H., Samuels, G. M., Dworsky, A., & Patel, S. “Missed Opportunities: LGBTQ Youth Homelessness in America.” Voices of Youth Count. 2018, Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago. Accessed 18 May 2023. https://www.chapinhall.org/wp-content/uploads/VoYC-LGBTQ-Brief-FINAL.pdf National Coalition for the Homeless. “LGBTQ Homelessness.” Nationalhomeless.org. 2017, Washington DC. Accessed 18 May 2023. https://nationalhomeless.org/wp-content/uploads/LGBTQ-Homelessness.pdf Wilson, Bianca D. M., Choi, Soon Kyo, Harper, Gary W., Lightfoot, Marguerita, Russell, Steven, & Meyer, Ilan H. “Homelessness Among LGBT Adults in the U.S.” Williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu. 2020, Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute at the University of California in Los Angeles. Accessed 18 May 2023. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/LGBT-Homelessness-May-2020.pdf

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|

© COPYRIGHT 2018. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|